Ultra-High-Net-Worth (UHNW) individuals – typically defined as those with over $30 million in liquid assets – present unique challenges and risks in anti-money laundering (AML) compliance. Financial institutions value UHNW clients for their business, but regulators worldwide are tightening expectations to ensure that wealth management is not exploited for illicit finance. This comprehensive guide explores why UHNW clients pose special AML risks, what global regulators (from FinCEN and FATF to the FCA and MAS) expect, and how firms like RIAs, private banks, family offices, and wealth managers can implement best practices. We’ll also highlight real enforcement cases and provide a practical compliance checklist.

Why UHNW Clients Pose Unique AML Risks

UHNW clients often have complex financial footprints that differ greatly from retail banking customers. These factors contribute to higher inherent AML risk:

- Complex Ownership Structures: Many UHNW individuals hold assets through layered trusts, offshore companies, special purpose vehicles (SPVs), family offices, or other entities that obscure the true owners. Illicit actors can exploit such complexity to hide their involvement. For example, U.S. authorities have noted that some investment advisors and private funds were used as entry points to channel illicit proceeds from foreign corruption and sanctioned oligarchs into the financial system. Unwinding convoluted ownership structures to identify ultimate beneficial owners is a major due diligence challenge.

- High-Value Assets & Alternative Investments: Wealthy clients often invest in assets like fine art, luxury real estate, yachts, private jets, precious metals, or cryptocurrency. These high-value assets are sometimes used to store and transfer value outside traditional bank accounts. The art and luxury goods markets, in particular, have minimal transparency and have been identified as vulnerable to money laundering. Without careful scrutiny, a client’s purchase of a million-dollar painting or a series of crypto transfers could mask illicit fund movements. Financial institutions must consider how to track and risk-assess such non-traditional assets.

- Cross-Border Activity: UHNW individuals are typically global citizens. They may have multiple residences, citizenships, or business operations across jurisdictions. Funds might move through offshore financial centers, and accounts could be spread worldwide. This cross-border exposure complicates AML controls: firms must navigate differences in jurisdictional regulations and detect when money moves through secrecy havens. Large cross-border wire transfers, private banking in high-secrecy jurisdictions, or frequent fund flows between countries are all red flags that require enhanced monitoring.

- Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) & Reputational Risk: A significant number of UHNW clients (or their close associates) qualify as PEPs – for instance, they could be senior politicians, officials, or linked to government contracts. By definition, PEPs carry higher risk of bribery and corruption, so banks are required to apply enhanced due diligence to them. In the European Union and UK, this scrutiny extends even to domestic PEPs (not just foreign officials), mandating EDD for local prominent individuals as well. The presence of a PEP in an UHNW client’s ownership structure elevates risk and often means the relationship must be approved at the highest levels of the institution. Even non-PEP millionaires can pose reputational risks if their wealth stems from sensitive industries (e.g. gambling, weapons) or if they are in the news for legal troubles. Firms managing such clients need to be vigilant about negative media and potential sanctions exposure.

In short, the very attributes that define UHNW individuals – large financial footprints, global reach, use of private investment vehicles – also create avenues that money launderers and bad actors can exploit. Recognizing these risk factors is the first step in mitigating them.

Global Regulatory Expectations for UHNW AML Compliance

Regulators around the world have raised the bar for overseeing wealthy clients, emphasizing a risk-based approach and stricter due diligence. Key expectations from major regulatory bodies include:

- United States (FinCEN and SEC): In the U.S., regulators are closing gaps in coverage to address risks in the wealth management sector. The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) recently finalized a rule extending AML/CFT program requirements and suspicious activity report (SAR) filing obligations to certain investment advisers. This was driven by findings that investment advisers have been used to funnel illicit wealth from foreign corruption, fraud, tax evasion, and even funds controlled by sanctioned individuals (such as Russian oligarchs) into the U.S. Banks and broker-dealers were already covered under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), but now family offices and wealth managers operating as registered investment advisers must implement due diligence and monitoring programs. U.S. expectations include identifying beneficial owners of accounts, verifying sources of funds, and filing SARs on any suspicious activity. FinCEN and federal banking regulators expect a risk-based program commensurate with the size and complexity of the institution – meaning UHNW clients, by virtue of higher risk, should receive commensurately greater scrutiny.

- International Standards (FATF): The Financial Action Task Force sets the baseline standards that many jurisdictions follow. FATF recommends that financial institutions apply Enhanced Due Diligence for high-risk customers, which explicitly includes PEPs and those in high-risk countries or involving unusual transactions. A core FATF principle is to know the beneficial owner behind legal entities and arrangements. This means that if an UHNW client uses a holding company or trust, a firm should identify the real person pulling the strings. FATF also emphasizes ongoing monitoring – not a one-time check. Countries that follow FATF guidance (virtually all major financial centers) have incorporated these principles into their local laws. For example, FATF Recommendation 12 requires obtaining senior management approval, source-of-wealth information, and enhanced ongoing monitoring for PEP customers. While FATF is not an enforcement agency, its guidelines heavily influence regulators like the MAS, FCA, and others discussed below.

- United Kingdom & European Union (FCA and EU Regulations): The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and EU regulators enforce some of the world’s strictest AML requirements for private banks and wealth managers. Under the UK Money Laundering Regulations (which implement EU directives), firms must treat even domestic politically exposed persons as high-risk, requiring the same EDD measures as for foreign PEPs. Banks must “exercise caution when dealing with PEPs due to the higher risk of bribery and corruption”, and if serious risks emerge, they are empowered to exit the client relationship even without providing a detailed explanation. The regulatory expectation is that source of wealth for UHNW clients (especially PEPs) is thoroughly verified and documented. The UK is also introducing tougher laws; a proposed Economic Crime Bill would make it a criminal corporate offence to fail to prevent money laundering. This puts additional pressure on banks – if a wealth manager turns a blind eye to a client’s dubious funds, the firm itself could face criminal liability. Across Europe, the AML directives (5AMLD/6AMLD) have brought new sectors under AML supervision (including art dealers and cryptocurrency exchanges), reflecting the concern that high-value transactions often linked to UHNW individuals need oversight. Regulators like the FCA conduct periodic thematic reviews of how private banks manage financial crime risk, and sizable fines have been levied for lapses such as inadequate due diligence on wealthy clients’ accounts (in some cases involving family members of corrupt foreign officials).

- Singapore & Asia (MAS, HKMA, etc.): Singapore’s Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and other Asian regulators have likewise honed in on private banking. MAS Notice 626 (for banks in Singapore) and similar regulations in Hong Kng require rigorous customer due diligence, with particular attention to wealth sources and PEP connections. MAS has not hesitated to punish banks that failed to control risks in ultra-wealthy accounts. In fact, in the aftermath of the 1MDB scandal – where billions in illicit funds flowed through bank accounts of a sovereign wealth fund – MAS took the unprecedented step of shutting down two private banks in Singapore. Swiss-based BSI Bank’s Singapore branch was ordered closed in 2016 for failing to control money-laundering activities connected to 1MDB. Shortly after, Falcon Private Bank’s license in Singapore was also withdrawn for similar breaches. These enforcement actions sent a clear signal that regulators expect full compliance even when politically connected billionaires are involved. Hong Kong’s HKMA and Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) have likewise imposed heavy penalties on institutions that ignored red flags with affluent clients. Across Asia, the message is that private banks and family offices must not let “safe harbor” reputations turn into safe havens for dirty money.

- Other Jurisdictions: Canada’s FINTRAC, Australia’s AUSTRAC, Switzerland’s FINMA, and others all follow the same general principles. Many have conducted high-profile investigations into wealth management misconduct. Switzerland, known for its private banking, has tightened oversight via FINMA; for instance, FINMA penalized banks that facilitated money laundering for South American PEPs and even temporarily barred one bank from acquiring new business until its AML controls improved. The common thread globally is an expectation of enhanced scrutiny, documentation, and monitoring for UHNW clients. Regulators coordinate through international bodies and share typologies (e.g., FATF papers on the misuse of corporate vehicles or the Egmont Group’s case studies) to ensure that no region becomes a weak link.

In summary, whether a firm operates in New York, London, Singapore or Zurich, the regulatory outlook is converging: UHNW clients must be treated as high-risk unless proven otherwise. Compliance programs should be adapted to meet both the letter and spirit of these global standards.

Enhanced Due Diligence: Source of Wealth and Funds Verification

Given the elevated risks, onboarding an UHNW client is not business-as-usual – it demands Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD) above and beyond standard KYC procedures. EDD for UHNW individuals centers on thoroughly understanding where their money comes from and who is behind it. Key components of this enhanced scrutiny include:

- Source of Wealth (SoW) Verification: Source of wealth refers to the origin of the client’s overall wealth – essentially, how they earned or accumulated their fortune. For UHNW clients, this often spans decades and multiple ventures. Was the wealth generated from a successful business sale, years of executive compensation, inheritance, or perhaps through investments? The institution should obtain documentation to support the narrative. This could include sale agreements (if a company was sold), audited financial statements of businesses, tax returns, proof of inheritance (wills or trust documents), investment portfolios, or real estate sale records. The goal is to corroborate that the client’s wealth was derived from legitimate activities. Regulators expect a level of detail commensurate with the risk: simply accepting a one-line declaration like “wealth from business proceeds” is not enough without evidence. If any aspect of the client’s story doesn’t add up – e.g., the client claims wealth from a tech startup sale but public records show the company was small – that discrepancy is a red flag. Indeed, U.S. authorities have noted that without insight into a customer’s identity and source of wealth, institutions are “not well-positioned to assess whether funds ... may be derived from illicit proceeds”. Thus, obtaining and analyzing source-of-wealth information is a fundamental control to prevent laundering of ill-gotten gains.

- Source of Funds (SoF) Checks: While source of wealth looks at the big picture of a client’s money, source of funds focuses on the origin of specific assets or transactions being brought into the institution. For example, if an UHNW client is depositing $5 million into an investment account, the bank should know where those exact funds came from (e.g., the proceeds of a stock sale last month, a dividend from a family business, a loan from another bank). For ongoing account activity, this means scrutinizing large or unusual transactions. If a client suddenly transfers €1 million from an account in a known secrecy jurisdiction, the institution should investigate the purpose and source of that transfer. Are the funds coming from the client’s own legitimate account or business, or could they be funnelled from a third party? Robust source of funds checks help ensure that even if a client’s overall wealth is legitimate, they aren’t acting as a conduit for someone else’s dirty money in individual transactions. This is especially relevant for clients who might allow their personal investment vehicles to be used by associates or family members.

- Comprehensive Beneficial Ownership Identification: With complex trust or company structures, an essential part of EDD is identifying all the real parties behind the account. For each legal entity (be it a trust, holding company, LLP, foundation, etc.) in the client’s structure, the institution should determine the beneficial owners (who ultimately own or control it) and any other controlling persons (settlors, trustees, board members, etc., in the case of trusts and foundations). This often requires obtaining corporate registries, trust deeds, organizational charts or letters from lawyers. It’s not uncommon for a wealthy family to have dozens of interlinked entities. The risk is that one of those entities could be co-owned by an undisclosed third party or could be in a jurisdiction known for anonymous shell companies. Notably, global regulators have zeroed in on beneficial ownership transparency; banks are expected to pierce through any “opacity” in ownership or else refrain from business. For instance, if a client’s family office is investing on behalf of several relatives, the bank should know who those underlying investors are. If the client is using an intermediary (lawyer, external asset manager), the institution must ensure that does not shield the true owners. The FATF standards and most national laws require that you cannot simply accept a shell company at face value – you must identify the humans behind it. This is time-consuming but critical: many past money laundering scandals (from 1MDB to various tax evasion schemes) involved wealth hidden behind nominee companies or secret trusts.

- Adverse Media and Reputation Checks: EDD also involves a deep dive into the client’s background via public domain searches and databases. Any negative news – allegations of fraud, past regulatory fines, criminal investigations, association with criminals – should be unearthed and evaluated. Wealthy individuals may have public profiles, so adverse media screening is essential. A client might not be officially listed as a PEP or sanctioned individual, but if investigative journalists have linked them to, say, a major corruption scandal (even without charges), the institution must factor that risk in. There are numerous cases of UHNW individuals who appeared respectable but were later revealed to be involved in money laundering or bribery (for example, certain billionaire art collectors or real estate moguls tied to kleptocracy). Thus, no stone should be left unturned: firms often use specialized due diligence reports from third-party providers to cover litigation history, source-of-wealth corroboration, and media profile as part of the onboarding package for an UHNW client.

Performing this level of due diligence can feel intrusive to clients and is resource-intensive for institutions. However, it is a non-negotiable expectation today. Regulators in multiple jurisdictions have explicitly required obtaining source-of-wealth information for high-risk clients (with PEPs as a prime example). In practice, this means compliance officers sometimes have to ask very direct questions and request private financial documents. A consultative approach can help – explaining to the client that these steps are required under law and for the safety of both the client and the institution. Some UHNW clients will push back, especially if they are used to Swiss banking secrecy or have never had to provide such detail. Firms should be prepared to stand their ground or even turn away clients who refuse transparency. The cost of onboarding a risky, non-cooperative millionaire is simply too high in the current enforcement climate.

Risk Scoring and Ongoing Monitoring for UHNW Accounts

Beyond upfront due diligence, managing UHNW clients requires continuous risk assessment throughout the relationship. A one-time check at onboarding is not sufficient, as circumstances and risk factors can change. Two core components of ongoing risk management are dynamic risk scoring and tailored monitoring:

- Risk Scoring and Risk Rating: Financial institutions use risk scoring models to assign each client a risk level (for example, “Low, Medium, High” or a numeric score). UHNW clients will typically score high by default on many models because of factors like large transaction volumes, international exposure, and higher likelihood of being a PEP or having complex structures. However, a nuanced approach is important. Firms should ensure their risk scoring methodology includes indicators specific to UHNW profiles. Key risk factors to incorporate include:

- Involvement of offshore jurisdictions or shell companies in the client’s structure.

- The presence of any PEPs (either the client, a beneficial owner, or even close family members or associates who are PEPs).

- The client’s industry and source of wealth (e.g. someone whose wealth comes from gambling operations or defense contracts would warrant more caution than someone who earned it as a salaried tech executive).

- Transaction behavior expected: Will they be making cash deposits (usually rare for UHNW), moving money to third parties, investing in certain high-risk sectors?

- Negative news or past compliance issues.

- Tailored Transaction Monitoring: UHNW individuals conduct transactions that are orders of magnitude larger than retail clients, and their activity patterns are unique. Monitoring systems must be calibrated to this reality. A generic rule like “flag cash deposit over $10,000” is likely irrelevant for a billionaire (they rarely deal in cash deposits, and if they do, even $10k might be trivial in context). Instead, scenarios should be customized. Some examples:

- Unexpected activity relative to profile: If a wealthy client’s family office account suddenly sends a wire to a personal account in a country where neither the client nor their businesses operate, that’s unusual and merits investigation.

- Movement of funds to secrecy jurisdictions: Transfers to or from accounts in known offshore havens (Panama, Cayman Islands, etc.) or countries under sanctions watch should draw scrutiny, even if amounts are within the client’s normal range.

- High-value purchases or sales: If the client’s account is used to buy or sell assets like artwork, luxury boats, or planes, ensure these align with known wealth and have a legitimate purpose. For example, a pattern of buying art through third-party shell companies could be a typology for laundering (as identified in various leak investigations of illicit wealth).

- Payments to advisors or intermediaries: UHNWIs often use lawyers, brokers, or consultants. Large payments to such persons, or requests to pay on behalf of the client, should be checked to ensure they’re not disguising beneficiary information.

- Crypto transactions: If allowed by the institution, any significant conversion of funds into cryptocurrency or out of crypto should trigger review, given the higher risk of crypto being used to obscure fund origin.

- Suspicious Activity Reporting: High-risk clients often require a higher degree of suspicion to be reported. Compliance staff might hesitate to file a SAR on a powerful client, but regulators expect unbiased judgment. Multiple banks have learned this the hard way: for instance, failures to report suspicious activities of politically-connected clients have resulted in enforcement actions and reputational damage. It is critical that institutions establish clear internal escalation protocols so that if something looks off in an UHNW account, it gets promptly reviewed by the compliance committee and, if warranted, reported to authorities. The threshold for suspicion is not higher just because the client is wealthy; if anything, unusual transactions by such clients should be examined even more closely against their stated source of funds. Firms should cultivate a culture where relationship managers understand that even marquee clients are not exempt from the rules. Ultimately, filing a well-substantiated SAR (and potentially exiting the client) is far preferable to being caught in a scandal for willfully blind compliance.

Real-World Cases and Penalties Involving UHNW Clients

Regulators have imposed severe penalties on institutions that failed to manage the risks of ultra-wealthy clients. These cases illustrate the importance of robust AML controls for this segment:

- 1MDB Scandal – Private Banks Shut Down: One of the most striking examples comes from Singapore’s enforcement actions related to the 1MDB scandal. 1MDB was a Malaysian sovereign wealth fund from which billions were siphoned by corrupt officials and their associates. A number of private banks eager for this lucrative business turned a blind eye to glaring red flags. In 2016, the Monetary Authority of Singapore permanently shut down the local branches of two Swiss private banks, BSI Bank and Falcon Bank, for egregious AML failures in handling 1MDB-linked accounts. These UHNW accounts were controlled by politically exposed persons and moved huge sums with little economic rationale. Compliance staff either failed to challenge obviously suspicious flows or were ignored by bank management due to the profit from these clients. In addition to the revocation of licenses (a very rare action), other banks like DBS and UBS in Singapore were hit with large fines for their lapses in the same scandal. The 1MDB case underscores that regulators will apply the ultimate sanction – shutting a business down – if they find willful AML negligence, especially involving powerful clients.

- Russian Oligarchs and Sanctions Evasion: In recent years, Western authorities have focused on how sanctioned individuals and kleptocrats hide assets via wealth managers. For example, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, governments sanctioned dozens of oligarchs. It emerged that many had used family offices, hedge funds, and investment advisers to quietly move wealth into places like London and New York. The U.S. Treasury’s FinCEN noted that “billions of dollars” tied to sanctioned Russian oligarchs and their networks had flowed through U.S.-based investment advisers and funds. These findings were part of what prompted the expansion of AML rules to investment advisers. While specific enforcement cases are often kept confidential, we know that several banks and law firms have been investigated for helping oligarchs purchase things like art, real estate, or stakes in companies via complex layers. In one Senate investigation, an art auction house was revealed to have unknowingly facilitated $18 million in purchases by shell companies linked to a sanctioned Russian billionaire. The lesson is that UHNW intermediaries who fail to detect such deception can easily become entangled in enforcement actions, facing hefty fines or legal action for sanctions breaches.

- European Private Banking Fines: Across Europe and the UK, there have been multiple fines related to wealth management clients. In the UK, the FCA has fined banks for inadequate due diligence on “source of funds” for wealthy foreign nationals investing in London property (a magnet for laundered money). One high-profile UK case involved a private bank that accepted politically connected clients introduced by third-party “fixers” without properly vetting their backgrounds – resulting in multi-million pound fines and public censure. Switzerland’s FINMA penalized Julius Baer, a major private bank, for failings including accepting suspicious Venezuelan and Russian funds; FINMA even took the unusual step of temporarily restricting Julius Baer’s growth until it remediated its compliance issues. In another case, a UK private bank, Coutts, faced scrutiny for alleged “de-banking” of a controversial PEP client (political figure Nigel Farage) – illustrating the fine line banks must walk between accommodating clients and managing risk. Meanwhile, Danske Bank in Denmark became Europe’s largest money laundering scandal when it was revealed that its Estonian branch handled over €200 billion in suspicious non-resident (often Russian) funds, many linked to wealthy individuals and shell companies. That scandal led to investigations across the EU and US, and Danske received penalties and settlements totaling in the billions of dollars. The common thread is clear: whether it’s London, Zurich, or Singapore, banks that ignored risky UHNW accounts eventually paid a steep price.

- Family Offices and Investment Advisors Under Watch: Traditionally, single-family offices (managing one family’s wealth) operated with relatively little regulatory oversight. However, enforcement agencies have started paying attention to these vehicles, especially after incidents like the leak of the “Panama Papers” and “Pandora Papers” which showed how elites globally (including heads of state and business tycoons) use trusts and private companies to conceal assets. While there may not yet be a headline-grabbing fine against a family office, jurisdictions are expanding laws to cover them. In the U.S., as mentioned, investment advisers (including those catering to wealthy families) will soon be required to implement full AML programs. Any family office that effectively acts as a financial facilitator (e.g., moving client money into investments or banks) could face liability if it willfully turns a blind eye to money laundering. And multi-family offices or external asset managers have indeed been fined in some cases when they failed to verify clients’ identities or source of funds and thus enabled illicit transactions. The writing on the wall is that regulators see no reason that wealth management should be a loophole in the financial system.

These cases reinforce why robust AML compliance for UHNW clients is non-negotiable. The cost of failure is not only fines and legal costs but also irreparable reputational harm. A scandal involving just one or two wealthy clients can tarnish a firm’s image far more than hundreds of lower-profile cases. On the positive side, regulators have issued guidance on these risks, so the expectations are relatively well-known – meaning firms have the opportunity to implement controls proactively before they end up in an investigation.

Best Practices for Wealth Managers Handling UHNW Clients

Financial institutions and advisors that service UHNW individuals should adopt best practices that go above the minimum requirements. Below are key strategies and controls that RIAs, private banks, family offices, and wealth managers can implement to manage AML risk effectively:

- Adopt a Risk-Based AML Program: Firms should design an AML/CFT compliance program that explicitly addresses the risks of UHNW clients as a category. This means conducting a risk assessment of the business to identify how and where UHNW money laundering risks arise (for example, through trust accounts, private investment deals, or cross-border wires). Policies and procedures should then be tailored to mitigate those risks. A smaller RIA or family office might not have the same resources as a global bank, but it can still institute rigorous checks proportional to its activities. Regulators expect a risk-based approach, so higher-risk clients (like UHNW or PEPs) must have enhanced controls. This could include requiring dual-signoff or committee approval for onboarding, extra documentation requirements, and more frequent monitoring (as discussed earlier). Ensure that your written policies spell out what additional steps are required for high-risk clients.

- Comprehensive Client Due Diligence: When onboarding an UHNW individual, “CDD” must be truly comprehensive. This starts with basic identification (collecting passports, addresses, etc.) but quickly extends to mapping out the client’s wealth and business interests. For wealth managers and RIAs, this often means looking through the client’s entire asset portfolio – bank accounts, investment holdings, real estate, trusts, etc. Gather information on all key related parties: trustees, authorized signers, power-of-attorney holders, business partners, family members with access, and so on. Private banks should coordinate among internal teams (lending, investments, deposits) to consolidate knowledge about the client. It’s a best practice to create a detailed KYC profile document for each UHNW client, summarizing their background, wealth origin, anticipated account activities, and risk factors. This profile should be accessible to anyone who needs to review unusual transactions or periodic updates. Essentially, anyone looking at that profile should understand the client’s financial story well enough to spot if something falls outside the narrative.

- Enhanced Verification of Wealth and Funds: As emphasized, don’t just take the client’s word for it on how they made their money. Verify it. This is where best-in-class institutions differentiate themselves. They will, for instance, use open-source intelligence and databases to verify a client’s company sale value if the wealth came from selling a business. If the client claims to own real estate worth $50 million, a bank might check property records or request appraisals. For investment income claims, asking for account statements or auditor letters is reasonable. Some banks require a written wealth declaration form from the client, which lists all major sources of wealth and accompanying documents. Then the bank’s compliance team cross-checks this against independent sources. By doing this, not only does the institution protect itself, it often uncovers inconsistencies or risk indicators early on. If something doesn’t verify, that’s a cue to dig deeper or even exit the onboarding. Remember that high-risk clients often have high incentive to misrepresent information, so a healthy skepticism is warranted.

- PEP and Sanctions Screening Processes: All the institutions in this space should use robust screening tools to check clients and connected parties against PEP lists, sanctions lists, and watchlists at onboarding and regularly afterward. This includes screening the names of any corporate entities (for sanctions or ownership by sanctioned parties) and any known associates. Given that UHNW individuals might show up in news or leaks, having a subscription to databases like World-Check, Dow Jones, or Factiva for adverse media is advisable. A best practice is to screen not just at onboarding, but continuously (either daily or at least monthly updates) because a client’s status can change overnight – today’s respected businessperson could be tomorrow’s sanctioned individual if geopolitical winds shift. If a client is identified as a PEP, follow regulatory requirements: obtain senior management approval for the account, establish source of wealth (which should be documented as discussed), and ensure enhanced monitoring. Document the rationale for any risk acceptance. Some firms choose to avoid PEPs altogether due to the complexity; those who do take on PEP clients need very strong controls to justify it to examiners. Similarly, if any hit comes up for sanctions (e.g., a client company becomes 50% owned by a sanctioned person), the firm should have an immediate escalation procedure to address it (which may involve freezing assets or off-boarding to comply with law).

- Tailored Risk Scoring and Client Risk Reviews: Use a formal risk scoring model that accounts for UHNW factors. For instance, you might add specific risk score points if the client uses a personal investment vehicle (since FinCEN has pointed out those can be abused by bad actors), or if the client has a complex trust structure spanning multiple countries. Make sure the scoring isn’t a one-time set-and-forget – incorporate triggers to re-score the client if certain events happen (like new adverse media, or the client engages in a new activity like crypto trading). High-risk clients should be subject to annual (or even more frequent) KYC refresh. In these refreshes, compliance should reach out to the client for updated information, check for any new corporate registry info, and update the risk assessment. It can be helpful to have a “client risk committee” that meets quarterly to discuss any material developments in top high-risk client accounts. This keeps attention from drifting and ensures accountability.

- Ongoing Transaction Monitoring and Controls: Implement monitoring that is proportionate to the size of transactions and the nature of the client’s activity. This might involve setting bespoke rules or thresholds for a particular client (many modern AML platforms allow customer-level tuning). For example, if a client normally sends wires of $500k to $1M as part of their investment activities, you might set a rule to flag if they send >$5M in one go to a new beneficiary, or if they break up transfers in a way that’s inconsistent with their usual pattern. Another best practice is conducting retroactive reviews of account activity as part of periodic risk assessments. Every year, take a look at the aggregate flows in the UHNW client’s accounts: Does everything align with known income events or declared uses of funds? If a client’s account saw $100M pass through in the year, can you match that to known sources (e.g., $80M came from sale of a business we knew about, $20M from investment income, etc.)? If there are gaps, that’s a sign further investigation is needed. Additionally, ensure that any large cash transactions or bearer instrument movements (if those still occur) are strictly controlled or ideally discouraged – wealthy clients should have little need for cash in modern finance, and if they insist, it’s a warning sign.

- Training and Culture in the Organization: Frontline staff like relationship managers, private bankers, and investment advisors should receive targeted training on the risks and red flags specific to UHNW clients. They are the first line of defense and also potentially the weakest link if they become too cozy with the client. Train them on scenarios like: what to do if a client asks “can’t you just skip this KYC question?”, or if the client tries to use influence (e.g., “I’m a major depositor, you don’t want to annoy me”). They need to know management will back them up for enforcing requirements. A culture of compliance is critical – one where performing due diligence is seen as protecting the firm’s franchise, not as unnecessary bureaucracy. It helps to share typologies and past cases internally to illustrate the very real risks (for instance, showing how a prestigious bank got in trouble for dealing with an art-collecting client who turned out to be laundering money). Also, consider implementing a “four-eyes principle” for interactions with high-risk clients: important due diligence decisions or waivers (if any) should require at least two people’s agreement (e.g., the relationship manager and a compliance officer). This reduces the chance of a single employee being pressured or misled by a client.

- Independent Reviews and Testing: Given the complexity of UHNW accounts, institutions should periodically have an independent party review their AML controls in this area. This could be as part of the internal audit function or an external consultant specializing in financial crime. Such a review would, for example, sample a few UHNW client files to see if source-of-wealth documentation truly supports the funds, if the risk scoring model was applied correctly, and if monitoring alerts were handled properly. It’s better to find and fix any gaps in a proactive way than for examiners or law enforcement to find them. Regulators often explicitly ask during exams about how the firm manages its highest-risk relationships, so being able to demonstrate that you regularly test and improve your processes is a strong positive.

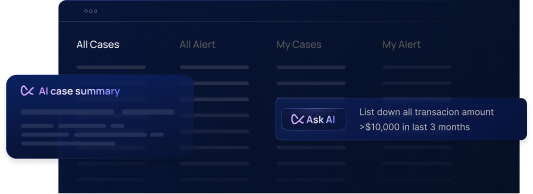

- Leveraging Technology and Data Analytics: Managing the voluminous data associated with UHNW clients (multiple accounts, entities, transactions across jurisdictions) is a challenge. This is where modern RegTech and fintech solutions can be game-changers. AI-driven analytics tools, for example, can sift through transaction patterns more holistically, linking seemingly disparate activities across accounts or spotting anomalies that rule-based systems might miss. For instance, an AI system might learn the typical behavior of a particular family office and then flag when a new pattern emerges that doesn’t fit (maybe subtle signs of account takeover or external infiltration). Technology can also assist in the KYC process: there are tools to automate the gathering of corporate registry data, to screen adverse media in real-time, and even to calculate risk scores dynamically as new data comes in. Using a centralized platform that consolidates all customer due diligence information, documents, and monitoring alerts in one place is extremely helpful for oversight (so that nothing falls through cracks between siloed teams). Smaller firms that may not have in-house tech can consider outsourcing some due diligence tasks or using compliance-as-a-service providers for things like background checks.

By implementing these best practices, financial institutions can create a robust defensive shield. It not only keeps regulators satisfied but can also become a selling point with clients – many legitimate UHNW individuals want to bank with institutions that take compliance seriously, as it protects them as well from unwitting association with financial crime. Moreover, a strong compliance framework allows a firm to grow its UHNW business confidently, knowing that risks are identified and managed, not ignored.

AML Compliance Checklist for UHNW Client Onboarding & Management

To translate the above into action, here is a practical checklist that compliance officers and risk managers can use when dealing with ultra-high-net-worth clients:

- Identify All Beneficial Owners and Controllers: For any account or entity related to an UHNW client, list out the ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs), signatories, trustees, board members, or anyone with control or interest. Ensure official ID documentation is collected for each person.

- Perform Thorough PEP & Sanctions Screening: Screen the primary client and all associated persons/entities against up-to-date PEP lists, sanctions lists, and known adverse media at onboarding. If any hits are found, escalate for detailed review and decision. Schedule recurring screenings (e.g., daily automated batch screening) to catch new designations or alerts over time.

- Obtain Source of Wealth Documentation: Require the client to provide a detailed explanation of their wealth and back it up with documents. This could include: financial statements of businesses sold, proof of inheritance (probate documents), investment account performance reports, etc. The documentation should reasonably account for the major portion of the client’s $30M+ net worth.

- Verify Source of Funds for Initial Deposit/Transactions: For the first significant funds that the client brings in or any sizable early transactions, trace the origin. If they transfer $10 million from another bank, obtain a reference or statement from that bank (and ensure that bank is reputable). If funds come from a sale of an asset, get the sale contract or closing statement. Do not accept large mystery wires with no context.

- Conduct Adverse Media and Internet Searches: Research the client’s name (and key related persons) in search engines, legal databases, and media archives. Look for any news of lawsuits, regulatory actions, or controversies. Document any findings and evaluate if they pose a risk (e.g., accusations of fraud, involvement in political scandals, etc., would elevate the risk profile).

- Risk-Rate the Client and Apply EDD Measures: Using your institution’s risk scoring methodology, classify the client’s risk level. Given the factors, UHNW clients will often be “High” risk. Apply corresponding enhanced due diligence measures such as: senior management approval for onboarding, more frequent reviews (at least annually), and placing them on a watchlist for compliance attention.

- Obtain Senior Management Sign-Off: Especially if the client is high-risk (PEP, complex offshore structure, high adverse media hits, etc.), have a formal approval by a high-level committee or senior compliance executive before finalizing the onboarding. Document the rationale for accepting the risk and any conditions imposed (e.g., “client will provide updated financials every year” or “account will be closed if political position changes”).

- Set Up Customized Monitoring Rules: As part of the onboarding, coordinate with your AML monitoring team to calibrate transaction monitoring for this client. Based on the expected account activity (which the relationship manager should help outline), set appropriate alert triggers. For example, if the client shouldn’t need to send money to personal accounts abroad, flag any such transfers. If they typically make investments under $2M, flag transactions above, say, $3M or multiple transfers just under $2M. Essentially, tailor scenarios to the client’s profile.

- Document the Client Profile & Due Diligence File: Compile a comprehensive KYC file that includes all the forms, copies of passports, corporate structure diagrams, source of wealth summary, verification documents, and the risk assessment. This file (physical or digital) should be organized and stored where it’s accessible for audits or regulatory inspections. A written narrative is helpful – summarizing how the wealth was obtained and the expected account usage. This will be invaluable when reviewing the account later or if a new compliance officer takes over the review.

- Provide Relationship Manager Guidance: Inform the front-facing advisors of any limitations or watch-outs (for instance, “we have not been able to verify XYZ business yet, so if client mentions it, collect more info” or “any request to add a new signatory must go through compliance due to high risk”). Make sure they understand the need to communicate changes in the client’s situation. Often RMs will know if a client is planning a big move (like selling a company or buying a new asset) – that info should be passed to compliance in advance to prepare for resulting fund flows or new due diligence needs.

- Ongoing Monitoring & Review Schedule: Mark the calendar for the client’s first periodic review (e.g., 12 months from onboarding, or sooner if higher risk). Instruct the compliance team on what should trigger an interim review (e.g., news event, an alert that was generated, etc.). Ensure that transaction monitoring alerts related to the client are not dismissed without senior analyst oversight, given the risk level.

- SAR Decision Protocol: Pre-establish the protocol for evaluating any potential suspicious activity in the account. Given the high stakes, maybe any SAR decision involving an UHNW client should be reviewed by the head of compliance or legal counsel. This ensures proper deliberation. If filing is needed, do it timely and without tipping off the client (as per legal requirements). Conversely, if deciding not to file on something borderline, record the justification (in case examiners question it later).

- Stay Current on Regulatory Changes: Assign someone to keep track of any new regulations or guidance specifically impacting wealth management. For example, the team should be aware of FinCEN’s updated rules for investment advisors or any new lists (like the US creating a list of “oligarchs” or the EU expanding the scope of regulated entities). Integrate any new requirements into the procedures for UHNW clients.

- Leverage External Expertise if Needed: If the client’s profile is particularly complex or outside the firm’s expertise (say, a billionaire art dealer with a labyrinthine network of shell companies), don’t hesitate to bring in outside help. This could mean hiring an investigative due diligence firm to do a deep background check or consulting with an AML expert on how to handle certain risks. The cost is often minor compared to the risk exposure of getting it wrong.

This checklist can serve as a baseline to ensure nothing critical is overlooked when bringing on a new UHNW client or maintaining an existing one. It should be adapted to each institution’s specific context, but the overarching principle is thoroughness and vigilance at every step.

Conclusion: Leveraging Technology and Expertise to Manage UHNW Risks

Catering to ultra-high-net-worth clients will always carry elevated AML risks, but with diligent processes and the right tools, those risks can be effectively managed. The regulatory landscape makes one thing clear: private wealth institutions must be just as vigilant as retail banks, if not more so. By understanding the unique risk factors (from complex trust structures to high-value asset trades) and implementing robust EDD, continuous monitoring, and strong governance, firms can both satisfy regulators and protect themselves from becoming conduits for financial crime.

It’s equally important to recognize the role of technology and data-driven solutions in staying ahead of these challenges. An advanced compliance platform can greatly ease the burden of monitoring multifaceted UHNW accounts. This is where Flagright comes in as a key ally. Flagright is a scalable, AI-driven AML platform designed to streamline risk management for high-complexity clients like UHNWIs. It integrates automated risk scoring, real-time transaction monitoring, and comprehensive case management, allowing compliance teams to detect anomalies across large volumes of data that would be impossible to spot manually. For example, Flagright’s algorithms can automatically flag inconsistencies between a client’s stated source of wealth and their actual transaction behavior, or alert you if a client’s name appears in newly published negative news. The platform’s scalability means that whether you’re a boutique family office or a global private bank, you can tailor the system to your needs – adding new data sources, adjusting risk models, and scaling up monitoring as your UHNW client base grows.

Flagright can help financial institutions implement the best practices discussed in this article. Instead of combing through spreadsheets and disparate systems, your team can have a unified dashboard driven by AI insights, focusing attention where it’s needed most. This not only improves efficiency but also provides a strong audit trail to demonstrate to regulators that you have cutting-edge controls in place. The bottom line is that managing AML for UHNW individuals does not have to be a daunting manual process; with intelligent technology, it becomes a manageable, even strategic, function of your business.

Financial crime threats and regulations will continue to evolve, especially as bad actors target the paths of least resistance. By investing in a robust compliance infrastructure solutions like Flagright, wealth managers and financial institutions can stay one step ahead. They can confidently grow their relationships with ultra-wealthy clients, knowing they have the defenses to prevent abuse of their services. In today’s environment, such confidence is worth its weight in gold.

Does your compliance program have the visibility and agility to handle the complexities of UHNW clientele? Stay proactive and protected – contact Flagright to learn how we can help safeguard your firm while you continue to deliver elite service to your most valued clients.

.svg)